Funcore, Happy Gabber, Tartan Techno

3 - Significant

Happy Hardcore, Hardcore

Happy Breakbeat, Gabber

Happy Hardcore, UK Hardcore

Bouncy techno was born in circumstances equivalent to its sound: Bass Generator double dropping happy breakbeat and gabber tracks to trick Scottish ravers into listening to mainland hardcore. Perhaps the most oft-forgotten era of happy hardcore, the genre's influence cannot be understated. Bouncy techno is, to put it simply, the lynchpin of modern hardcore. It not only underpins the development of every major happy hardcore style from here on out, but can also claim to be the entire reason we even consider hardcore to be a single coherent umbrella.

Let's start at the beginning. In the beginning, there was happy hardcore. If you were a British raver in 1992, you knew happy hardcore as the sugary, mainstream derivates of house and breakbeat. Led by chirpy vocals and twinkling piano riffs, it was a style of music that proved immensely popular in the northern half of the UK while the south pivoted towards harder and darker sounds. If you were a mainland raver in 1992, you didn't know what happy hardcore even was, and if anyone told you, you'd probably be confused as to why it was being called hardcore. Breakbeat hardcore and hardcore techno had taken different paths; while both were, by and large, natural progressions from house and techno, they had unique origins, with breakbeat hardcore spinning out of Britain's nascent underground hip hop scenes and hardcore techno (along with gabber, acidcore, and all the other early eurocore sounds) being a more straightforward progression of acid house and acid techno. To put it simply, there was no unified hardcore in the early days. These were two entirely separate musical traditions, utterly unconnected to one another.

Scottish DJs had started to try to introduce heavier sounds to northern audiences by 1992, to little success. Things started to change when Bass Generator (aka Guy Kneeling) and Scott Brown (aka Scott Brown) became enamored with gabber and resolved to make Scottish ravers like it or die trying. The operation was simple. Step One: Bassy G (as at least one major Scottish mag referred to him) would begin sneaking gabber tunes into his sets. The audience wanted piano anthems, and piano anthems they received, but Guy would speed them up and drop them with gabber tunes, keeping the audience satisfied while indoctrinating them into a cult of heavier beats and faster tempos. Step Two: Scott Brown would concoct a potent new style, drawing from the strange happy gabber hybrid Bass Generator had developed and turning it into a coherent vehicle for original tunes. The operation was a resounding success, and together they established bouncy techno as a major sound in the British rave landscape.

Guy Kneeling standing.

This new sound was driven by two major elements: heavy gabber-influenced beatwork (primarily driven by distorted kicks that run the gamut from a decent thump to full on mild gabber kicks, albeit with a much shorter decay and release) and off-beat synth stabs. Together, these two sounds formed the trademark "bounce" of bouncy techno. It was heavy enough to satisfy British crowds looking for something more aggressive, but also more melodic and complex than most gabber of the time. This drew the attention of Paul Elstak, who began importing British bouncy techno tracks in 1994 for Dutch audiences that went mad for it, warping the entire path of the Dutch scene around it. The pan-European hardcore scene had been established with bouncy techno at the very center of it. In Europe, they called it happy hardcore - either unaware of the British meaning of the term, or misunderstanding bouncy techno's opposition to it - and dragged both ends of the British scene kicking and screaming into the wider hardcore landscape as pair of genres that were now inextricably linked as members of a unified happy hardcore umbrella.

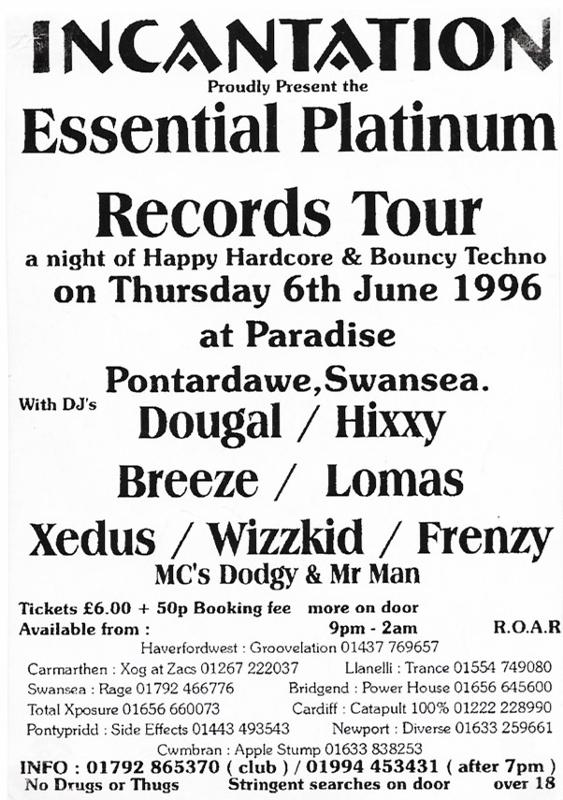

Flyer for an Essential Platinum event from 1996. Even after the Dutch established happy hardcore as a broader term for British-style hardcore music, happy hardcore and bouncy techno were understood to be entirely different things by British ravers.

Bouncy techno was at its peak from around 1994 to 1996. In the Netherlands, bouncy techno died a sad death as ravers eventually revolted against the lighter sounds of the genre, decrying not only the genre itself but also Paul Elstak for what the viewed as a betrayal of hardcore ethos by pursuing mainstream success. By 1997, gabber had entirely reasserted itself as the dominant form of Dutch hardcore, just in time to witness its grand transformation into nu style. In Germany, however, the sound exploded and became something much bigger than itself. Spurred by influences from eurodance and hard trance, German producers developed their own form of happy hardcore that retained the rhythms of bouncy techno but toned down the gabber roughness. This new sound became an international success, not only becoming arguably the single most iconic sound associated with the term happy hardcore for many people, but also largely wiping bouncy techno off the map. In England, bouncy techno was already on the way out by 1996 due to a mix of government intervention in the rave community and intra-scene burnout. By 1997, most bouncy techno producers had either begun transitioning into the newer German sound or dropped out of happy hardcore entirely.

And thus, bouncy techno was dead. At least, it was dead in its original form. Scott Brown frankenstein'd the genre out of its grave in 1998, pulling something much akin to the Germans before him and developing a new sound built on a bouncy techno foundation. This new sound, a fusion of bouncy techno's off-beat rhythms and the more contemporary anthemic sounds of trance, quickly found purchase as the earliest form of what we now know as UK hardcore, cementing happy hardcore's perpetual success by becoming so fluid and malleable as to be able to be combined with practically anything. In this manner, bouncy techno lives on, if not by its own popularity then by its lasting musical influence on modern happy hardcore and its wider cultural influence on the entire field of hardcore. Gone but never forgotten, bouncy techno oom-pah'd its way straight to hell and we're all better off for it. Godspeed.

Bass Generator - "The Event (Can I Have A Lime Top In My Shandy Andy? Mix)" from The Event (Or Is It?) (1993).

Paul Elstak - "Boom Boom (Whoo)" from Luv U More (1995).

Helix - "Get It Right" from Get It Right / Before Your Eyes (1996).

Antisocial - "Get Into Love" from Get Into Love / Whistle (1997).

Emoticon - "Nugget Resort" from Nugget Resort (2016).